Image from Museum of Idaho

Science News: What you want vs. what you get

A case study in wolf domestication:

Starch Metabolism Gene: MGAM

Image from Museum of Idaho

This web page was produced as an assignment for an undergraduate course at Davidson College.

Popular press is a mess:

The trouble with communicating to the layperson the flurry of scientific findings published each day is summarized nicely in an article written by Kua et al. scrutinizing popular press coverage of scientific progress: “attempting to move knowledge from the world of scientists into the public sphere presents real challenges to reporters and to newspapers that have to contend with limitations on space and reader interest” (2004) (emphasis added). Kua et al. assert that public press “science writers”, a suspect title, ought to supply readers with “the detail that will enable readers to make connections.” (319).

Perhaps it is unfair to expect popular press journalists to be as thorough and precise as is needed to adequately convey complex scientific happenings. Perhaps readers just won’t be interested, especially if an article spans several pages.

In the following case study, we will compare the original results of a genomic study of dog domestication to the portrayal of those results in an article posted on the National Broadcasting Company’s (NBC’s) website, originally published by HealthDay News. Throughout our analysis, we will focus on three general categories drawn from the many qualities of good science writing highlighted by Kua et al.:

Sniffing out the truth using research in dog domestication

On January 23rd, 2013, scientists Erik Axelsson et al. published an article in Nature describing the results of a comparison full of sequences of the domestic dog and the wild wolf (full article). Among the findings are a set of adaptive genes that are involved in the metabolism of starch, in particular MGAM (maltase glucoamylase), in which indications of selective pressure were identified. This selective pressure may have been the result of proximity to human beings and their food scraps, which leads the team to conclude that such pressure may have contributed to the eventual domestication of wolves. The following is a summary of the key points highlighted in the popular press article, as well as links to critical commentary explaining how the popular press article misses the context, methodology, and implications of the findings, as told by the complete report by Axelsson et al.

Popular Press:

“Why some wolves became dogs” (January 23rd NBC, orig. HealthDay News)

Summary of Key Points (full article)

The question of how dogs became domesticated has largely been answered by these findings. (commentary)

The researchers used a “complex genetic analysis and an understanding of archeology, ecology, biochemistry and agricultural science” to identify adaptive starch metabolism phenotypes as the key to domestication. (commentary)

The process of domestication was simple, and hinged upon genes for starch metabolism. (commentary)

Researchers compared the genomes of dogs and wolves. (commentary)

36 "targeted genetic regions" were identified, with 8 genes relating to the nervous system, and 10 to starch metabolism. (commentary)

The place in the genome at which mutations are located in dogs, and conserved across most dogs, those genes are likely critical to domestication. (commentary)

Humans and dogs may have responded to similar selective pressure with the expansion of starches in their respective diets. (commentary)

This study may shed light on the best mix of nutrients in dog food. (commentary)

Genomics Page

Biology Home Page

For a hybrid version of these accounts which hopes to resolve some of the shortcomings of popular press without the complexity of the original article, click here

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________

1. "The question of how some wolves...evolved has remained largely unanswered. Until now" (HealtDay News). This grandiose phrasing is an example of the tendency for the popular press to sensationalize scientific findings for the sake of grabbing the attention of the readers. A much more moderate expression of the results can be found in the "abstract" of the original article in Nature, a section in most scientific articles that summarizes the topic, methodology, and results of the study succinctly: "Our results indicate that novel adaptations allowing the early ancestors of modern dogs to thrive on a diet rich in starch, relative to the carnivorous diet of wolves, constituted a crucial step in the early domestication of dogs" (Axelsson et al. 2013). Identifying a "crucial step" in the evolutionary process by which wolves evolved into dogs is indeed significant, but implying that the results of this study "largely" answers the mystery surrounding domestication misses the context of the findings, and further may set an unfair expectation in the mind of the reader that news releases about science will always report immense breakthroughs. Here the content of the original results is misrepresented.

2. The main work of the scientists was genome-wide analysis of specific locations in the DNA sequences of the wolf and dog, termed "loci". The researchers used some statistics and key database-driven tools to identify regions of DNA that show signs of encoding traits which selection processes rendered adaptive as wolves and humans interacted more often. Calling these regions “candidate domestic regions” (CDR’s), they used a database equivalent of looking up those genes on Google, finding that many fit neatly into the following categories: nervous system and development, sperm-egg recognition, regulation of molecular function, and digestion. This database-searching tool is called “Ensembl”, and is available at http://useast.ensembl.org/index.html. You will need to know the name of a gene to get started, so try this one out: MGAM. In the search results, find dog, and see the sidebar for information regarding the gene. The work relating to the other disciplines listed (archeology, ecology, etc.) was only referenced in the "discussion section" of the scientific article, where the researchers generally relate the context of their findings to implications within related inquiries and disciplines.

3. "The transition from wolf to dog was relatively simple"..."Axelsson said it's actually easy to envision how it might have happened" (HealthDay News). Perhaps to make the reader feel more confident, or perhaps to contribute to the illusion that these results are as monumental as is implied, these two statements grossly misrepresent the thoughts of Dr. Axelsson, who is quoted saying "Some wolves were slightly better than others at digesting starch and had an advantage. A natural selection process created animals that we later called dogs." In the context of this article, this statement seems to relate to the assertion above: Axelsson thinks the entire process by which wolves evolved into wolves was "simple", when what he is more likely saying that identifying the selective pressures leading to increased starch metabolism, as seen by increased the transcription of MGAM and other genetic modifications, is relatively simple to do. Instead of communicating the complexity of such the overall evolutionary process, which would accurately inform the public as to the full extent of the research process, this reduction warps the sense of scientific context that the reader receives.

4. What the article does nicely here is to follow with a sentence describing chromosomes as "representing all the inheritable traits of a single organism", a useful if incomplete definition. However, the meat of the findings described in the research paper is the identification of three genes that participate in starch metabolism and show signs of having been subjected to selection pressures. Among them is MGAM, or "maltase glucoamylase", which plays a role in metabolizing starch in several species. While the genes themselves aren't unique, it is the presence of unique combinations of MGAM and other genes near it, unique mutations within the DNA sequence for MGAM, as well as increased transcription of MGAM, that serve as evidence for selective pressures modifying the way dogs metabolize starch (see figure below). Understanding the nature of these findings requires knowing more than just that chromosomes contain heritable information. The brief explanation we have just made is a good start to laying an appropriate foundation upon which a reader can form an understanding of the findings.

Adapted from Axelsson, et al. (permission pending)

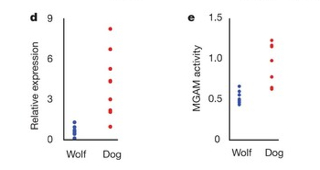

This figure shows one of the techniques that the researchers used to determine that MGAM has been modified in dogs during wolf domestication. Expression (left) is the process by which the product of a given gene is made. Because MGAM is expressed more often in dogs (red), and MGAM is directly involved in starch digestion, this is likely associated with domestication. MGAM activity (right) is also higher in dogs, showing that not only are the genes for starch metabolism modified in dogs, but functionally change their metabolism.

5. This information exists as a short, disjointed paragraph which uses terminology like "genetic variants" and "targeted genetic regions", with which a reader might not be familiar. Furthermore, these terms do not do enough connect the reader to the ensuing explanation of identifying regions with a high rate of mutation. Essentially, this is a dump of some impressive numbers. Instead of gaining a practical understanding of the implications of the findings, the reader is left to try and make sense of the numbers and the terminology. What the article does well here is point out that the researchers found regions of genetic interest relating to starch metabolism as well as neurological function. This begins to get at the crux of the findings, while pointing out that starch metabolism is not the only point of divergence between wolves and dogs.

6. This is by far the best paragraph in the article, which explains one of the methods by which the researchers determined that certain regions of the dog chromosome are different from their equivalent (orthologs) in the wolf as a result of selective pressures. The article explains that areas where their are many mutations, surrounded by areas with fewer mutations, are likely places where adaptive traits developed during evolutionary divergence. Adaptive traits arise when a mutation in a gene or many genes results in a new function of the gene product produced by that gene that is useful to the organism in its environment. Mutations in MGAM and related genes, as well as in genes responsible for enhancig its production, may have resulted in an increased ability for certain wolf individuals to digest starch. That MGAM features such genetic changes, and other genes around it don't, is good evidence to support the claim that selective pressure related to starch metabolism, such as access to human foodscraps, was a important factor in the evolution of wolves to dogs. What the article could have done to bring the reader up close to findings and drive home the understanding is to mention the specific genes and their funcitons. The genes are the focus of the findings, and at once properly cast the typical product of a study such as this while not setting unfair expectations for the findings as described above.

7. That humans and dogs may have responded to the same selective pressure in adapting to starch digestion is an intriguing conjecture made by the researchers. As stated by the popular press article "The researchers said that the study results show how coping with an increasingly starch-rich diet when humans began to grow their own food caused similar adaptive responses in dog and human" (HealthDay News). In reality, the researchers point out in their concluding paragraph that their results are a "striking case of parallel evolution whereby the benefits of coping with an increasingly starch-rich diet during the agricultural revolution caused similar adaptive responses in dog and human30", presumably one among many such cases. The citation that follows their statement refers the reader to a paper in which human MGAM genetics are indeed considered, as this group did not work with human genomes. This paragraph and that which follows in the popular press article are examples of such a forum for communicating scientific results misconstruing the results of the study to make the results seem more all-encompasing.

8. In the last paragraph, the popular press article devalues the importance of the findings by saying "While this may all sound quite academic..." (i.e. useless). The article proceeds by referencing a veterinarian who sees some potential for the metabolic insights identified by Axelsson and his team to be applied in creating more effective dog food. While similarly intriguing as the dog/human coevolution information (see above), this concluding paragraph minimizes any emphasis that was placed on the findings of this research itself, leaving the reader with a diminished view of the value of domestication research in itself.

Genomics Page

Biology Home Page

© Copyright 2013 Department of Biology, Davidson College, Davidson, NC 28035