TABLE OF CONTENTS

Introduction

CD4 T Cells Role in HIV Infection

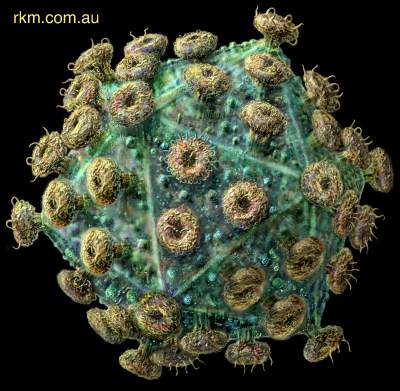

| Figure 1- HIV is approximately 1,000Å in diameter and the the basic surface structure consists of envelope proteins (shown in brown) that allow the virion to bind to target cells. This image is used with permission from the Aids Education and Research Trust (AVERT). <www.avert.org/virus.htm> |